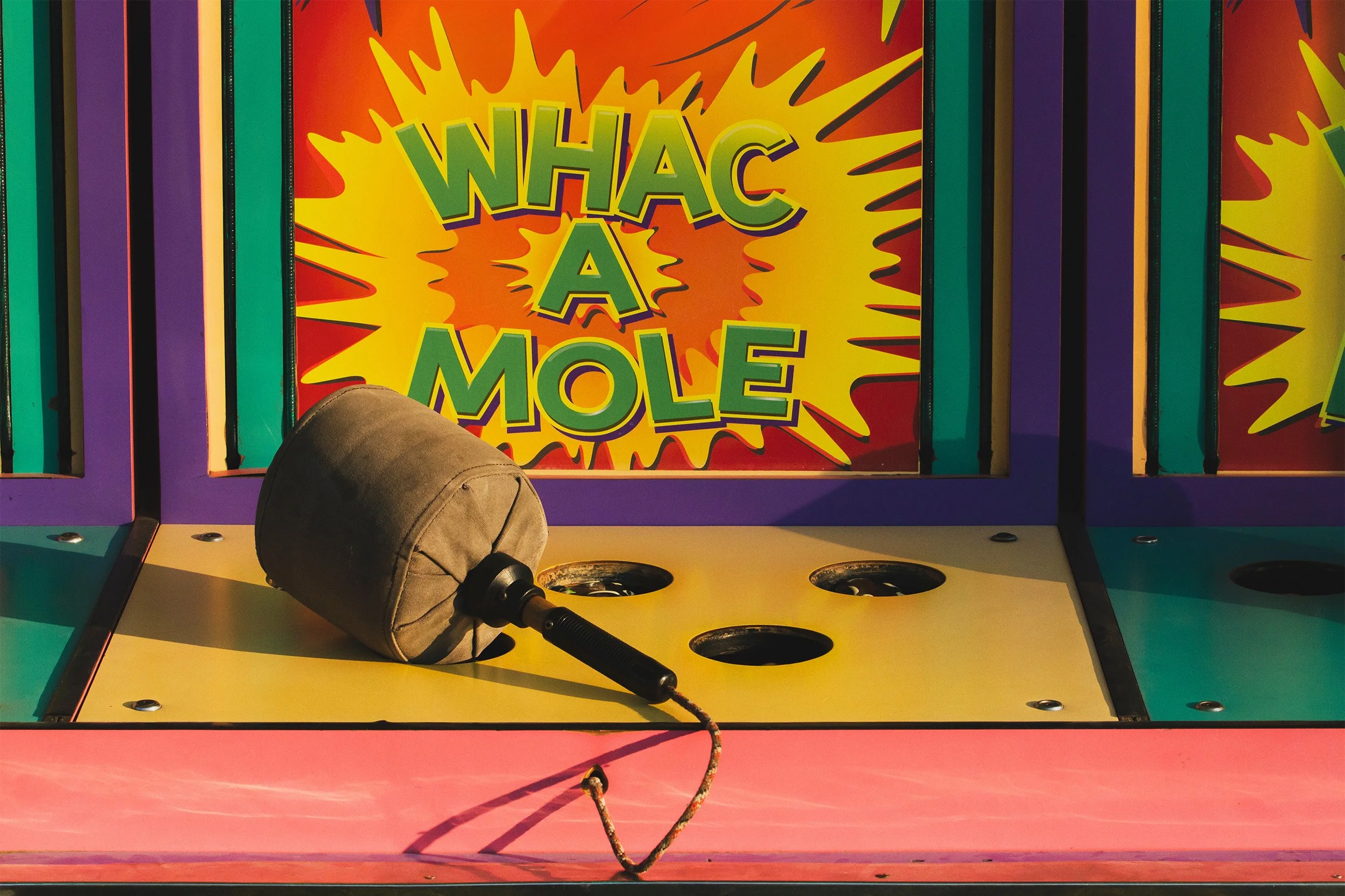

The Politics of Whack-a-Mole: Why San Francisco Doesn’t Solve Its Homelessness & Drug Problems

Why do we keep making sweeps the centerpiece of our City’s strategy to address homelessness and behavioral health, even when that strategy has proven year after year not to work? Simple: it benefits careerist politicians, whether it works or not.

During my five years as an elected official in San Francisco, I saw firsthand how politicians who know better shifted their approach from trying to solve homelessness and behavioral health problems to trying to sweep them out of sight, from one block to the next, or one neighborhood to another. I often think back to a neighborhood meeting in Haight-Ashbury years ago where Jenny Friedenbach, director of the Coalition on Homelessness, explained how politicians benefit from approaching social issues in the street like a game of whack-a-mole. I’m paraphrasing as I don’t recall her exact words, but the point stuck with me:

For a politician, sweeps are the gift that keeps giving.

A constituent calls: “There are homeless people in front of my house!”

The politician calls the police. The homeless people are moved a block over.

The constituent is happy. The politician wins their support.

But the homeless people aren’t getting housed, and now they are on the next block. So the politician gets a call from a resident on that new block: “There are homeless people in front of my house!” Another call to the police, and people are moved again. Another happy constituent, and the politician has won more support.

Rinse, repeat. Another call, another sweep. Another political win. It works exactly the same with public drug use.

A constituent calls: “I see people using drugs on my block!”

The politician calls the police. The user is arrested or displaced out of sight.

Another happy constituent, another vote for the politician, all the while the underlying crisis deepens. The activity moves to the next block, and people are still suffering without shelter or support.

So if the goal is to house people and end the cycle for good, the politician has completely failed. But if the goal is to create the appearance of success and win support, the strategy is very effective. It is the gift that keeps on giving – politically.

Jefferson Square: A Manufactured Crisis and Manufactured “Win”

The recent situation at Jefferson Square in the Western Addition illustrates the dynamic. Immediately after Daniel Lurie became mayor, his administration conducted extensive sweeps in the Tenderloin and SOMA neighborhoods, and displaced people moved to the neighboring Western Addition and Mission. By February, Jefferson Park had become a complete mess and residents understandably contacted their elected officials to complain.

Mayor Lurie, with support of the new D5 Supervisor, dispatched police to raid Jefferson Square Park, arresting 84 people. The media celebrated this with nonstop coverage, and Mayor Lurie and the supervisor claimed victory. But it’s important to understand the dynamic, not covered by the corporate media. First, these politicians created the problem in Jefferson Square Park by sweeping people from other areas, so they settled in the park. Second, the politicians didn’t solve anything, they just had a bunch of people arrested for using drugs, who upon release moved on to the next location. Third, the entire costly PR stunt makes it more likely those experiencing homelessness and addiction will overdose, lose the few possessions they have, experience trauma, and thereby stay homeless longer. So at the end of the day, the City spent a small fortune to sweep homeless people to the next block and make their lives worse off.

It is not even disputed that this is their mode of operating. In a recent hearing, Commander Derrick Lew addressing enforcement against public drug use downtown explained to the Board of Supervisors that “success in that area will clearly mean that there's some displacement.”

I think we can all agree that everyone is better off when activities like sleeping, bathing, cooking, urinating, defecating, and doing drugs do not take place in public. But too often, San Francisco’s approach to these difficult issues is to return to a failed strategy of large-scale enforcement against people -- even when they have nowhere else to go.

A Loss of Mission and Shift in Priorities

In recent years, the situation has gotten even worse. The punishment industrial complex, led by the right wing and fully supported by compliant SF Democrats, is an exceedingly well-funded network that has gathered strength since the pandemic and the 2020 civil rights uprising. Their goal is to blame the poor, fearmonger, troll and smear advocates for the vulnerable, and promote conservative “law and order” politicians.

The results have been striking. In the first few years I was in office, a top explicit goal of street outreach was to help homeless people get housing and support. Over the years, under Mayor Breed, as I raised in two hearings in 2024, the goal of ensuring a path to stable and supportive housing was stripped out from the “top tier goals” of the street teams, in favor of language focusing on the “quality of life” of those who are housed.

Same at the Department of Public Health, where the department that previously focused its behavioral health work on saving lives, preventing overdoses, and getting people into treatment, is increasingly forced to prioritize the experiences of housed neighbors as a central part of their work. DPH has retreated on its advocacy for overdose prevention sites, and removed concerns about racist outcomes from policing strategies from its overdose prevention plan.

We need leaders that see the problem with homelessness first and foremost as a humanitarian problem. We need leaders that see the problem with drug use that people are addicted and dying. Instead, our current leaders see the problem not as suffering itself, but the discomfort it causes housed residents. They focus on tents, trash, public urination or defecation, or people self-medicating with drugs or experiencing a mental health crisis, instead of addressing the roots of trauma caused by living on the streets.

Author and political scientist Lincoln Mitchell hits the nail on the head in his recent piece entitled Fentanyl Overdoses and the New Mayor:

It is now increasingly apparent that for Lurie, addressing the perception of disorder was a higher policy priority than helping people who are homeless or wrestling with substance abuse. In other words, like many affluent San Franciscans, Lurie has chosen to see homelessness and drug overdoses as a quality of life problems for affluent people like himself rather than humanitarian crises for those living on the streets, or for those, homeless or not, overdosing on fentanyl.

This was painfully obvious in Mayor Lurie’s inauguration speech, but many of us hoped those words were just designed to placate the pro-punishment crowd, and that he might take a more balanced approach than his predecessor. So far, it’s been the opposite.

As with so many issues, centering the most vulnerable does not offer political benefits in today’s media and political landscape. Those most vulnerable often do not vote. Nor is their perspective shared in the corporate media. But if leaders do not champion real solutions to homelessness and drug addiction, we are guaranteed to continue failing to solve these crises.